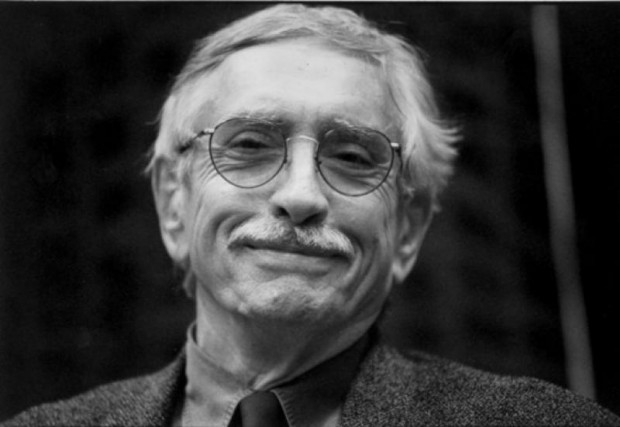

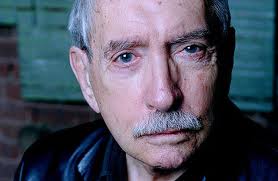

Joan Sellent, un dels grans traductors del teatre català, va tenir una desagradable experiència en traduir A Delicate Balance (Un fràgil equilibri), d’Edward Albee, per les humiliants exigències d’aquest autor i la seva hostilitat manifesta als traductors en general.

Passat un temps prudencial, Sellent li ha adreçat una carta, que ha estat molt ben rebuda per l’agent d’Albee, igualment exasperada i farta dels capricis despòtics de l’autor de ‘Qui té por de Virginia Woolf?’ A hores d’ara, Albee probablement ja ha rebut la carta de Joan Sellent, que avui publiquem a Núvol en català i en anglès.

Sabadell, 12 de juny del 2012

Benvolgut senyor Albee,

Deu fer cosa d’un any vaig rebre l’encàrrec de traduir la seva peça teatral A Delicate Balance per a un muntatge concret que es va estrenar a Barcelona la tardor passada, amb el títol d’Un fràgil equilibri.

Com ha estat sempre el cas amb les obres que he traduït per a l’escena, vaig assumir aquest encàrrec amb l’objectiu de ser el més respectuós possible. Crec que el respecte és una de les prioritats que un traductor sempre ha de tenir presents, i que aquest respecte té dos destinataris principals: d’una banda el text original (i, per extensió, el seu autor), i de l’altra els espectadors potencials de l’obra.

Quan ja havia enllestit la traducció d’A Delicate Balance se’m va informar de l’obligació de fer-li arribar, com a autor del text original, una exhaustiva “graella” de cinc columnes amb l’especificació detallada de —cito textualment del correu electrònic enviat per la seva agència— “qualsevol desviació de les paraules angleses exactes i l’explicació de per què no se’n va poder fer una traducció directa a l’espanyol, i per què es van triar les paraules que es van triar”.

Permeti’m que li exposi el principal motiu pel qual aquests requeriments van provocar-me l’impuls immediat de no perdre ni un sol minut a acatar-los: bàsicament em vaig sentir insultat com a professional en veure que, després de més de trenta anys de dedicar-me a la traducció, algú esperava que dediqués una part gens desdenyable del meu temps a una activitat tan absurda com inútil.

Pel que fa a la primera part del missatge citat més amunt —“qualsevol desviació de les paraules angleses exactes”—, li puc ben assegurar que, exceptuant els noms dels personatges i un parell de topònims o referències culturals, la resta de la meva traducció és una absoluta i radical desviació de les paraules angleses exactes, senzillament perquè està escrita en un altre idioma. Un idioma que, per cert, no és l’espanyol —com es diu erròniament a l’e-mail— sinó el català, una llengua que pertany a la família de les llengües romàniques i que té prou trets diferencials per conferir-li la condició de llengua autònoma en relació amb l’espanyol i amb qualsevol altra d’aquesta família. Imagini’s la llargada quilomètrica que hauria adquirit la graella si hagués decidit complir aquest requisit literalment.

Respecte a la part final de les seves exigències —“… per què es van triar les paraules que es van triar”—, podria limitar-me a argüir que la dubtosa oportunitat d’una pregunta com aquesta (pensi per un moment que algú que desconeix la seva llengua li fa aquesta pregunta a vostè en relació amb una obra seva) em fa més aviat reticent a contestar-la, però deixaré de banda l’amor propi i faré l’esforç: senyor Albee, les paraules triades van ser triades, simplement, perquè el traductor les va considerar apropiades.

Vostè tenia el perfecte dret de témer que hagués pogut triar unes paraules que traïssin o distorsionessin el sentit, la intenció, el to i el registre de l’original; no li diré que aquest temor sigui del tot injustificat, perquè no és pas que escassegin els traductors que maltracten i distorsionen qualsevol text que els cau a les mans, però ¿creu realment que, si jo fos un d’aquests, hauria explicitat les meves malifetes a la graella que se m’obligava a omplir?

Si finalment vaig cedir a les seves exigències va ser purament per amistat amb els productors del muntatge teatral, els quals m’havien fet saber que, si aquestes exigències no eren satisfetes, l’autor faria aturar els assajos i no permetria que l’obra s’estrenés (cosa que hauria infligit un greu revés econòmic a aquesta productora). Vaig perdre, doncs, deu o dotze hores de la meva vida empescant-me una sèrie de pomposes explicacions pseudo-filològiques a fi de poder omplir la famosa graella; dit d’una altra manera: vaig confeccionar una llista d’absurditats completament estèrils de la primera fins a l’última. El que li puc assegurar és que, si hagués estat al cas de les seves exigències abans de traduir l’obra, hauria declinat l’encàrrec sense pensar-m’ho dues vegades.

No sé si el que he dit fins aquí li pot fer sospitar que poso en qüestió el dret moral, intel·lectual i legal d’un dramaturg de tenir l’última paraula sempre que una obra seva està en procés de ser posada en escena. Si és així, m’afanyo a aclarir que no hi ha res més lluny de les meves intencions. Crec fermament que és decisiu i legítim que un dramaturg faci valdre la seva autoritat, sobretot en els temps que corren, en què proliferen els directors d’escena que, en lloc d’estar al servei del text, tendeixen a prendre’s unes llibertats difícilment justificables i a atorgar-se una suposada autoria que no els correspon. Aquest directors amb ínfules d’autor són, sens dubte, un dels flagells de l’escena contemporània.

I no cal dir que també considero absolutament legítim el dret del dramaturg de controlar les traduccions de les seves obres abans que arribin a la impremta o a l’escenari. Només faltaria. Hi ha moltes males traduccions que, amb els seus errors semàntics i les seves imperfeccions estilístiques, constitueixen una feixuga rèmora que sovint un determinat muntatge teatral ha d’arrossegar fins a l’escenari i que va en greu detriment del resultat final i de la recepció de l’espectacle per part del públic.

Això no obstant, quan algú decideix fer valdre els seus drets —i ara em refereixo a qualsevol àmbit de l’activitat humana—, penso que caldria esperar que el pragmatisme, el sentit comú i l’ètica més elemental l’inclinessin a fer-ho d’una manera intel·ligent i alhora útil per als seus interessos, i no pas únicament ofensiva per a la part que suposadament podria posar en perill aquests drets. L’experiència personal d’haver traduït aquesta obra de vostè m’ha fet veure fins a quin punt pot resultar lamentable l’autoritat quan s’exerceix d’una manera que no té absolutament cap altra utilitat que la d’humiliar gratuïtament un professional que ha procurat fer la seva feina tan bé com ha pogut.

I deixi’m ser una mica repetitiu: la manera que té vostè d’exercir la seva autoritat com a dramaturg —almenys pel que fa a les traduccions— és, des d’un punt de vista pragmàtic, completament inútil. Les graelles que vostè obliga els traductors a omplir no garanteixen en absolut la qualitat d’una traducció. ¿Creu sincerament que algú que ha fet una mala traducció pot ser capaç de detectar els seus propis errors i, suposant que això fos possible, seria tan insensat d’enumerar-los explícitament?

A fi de garantir uns resultats positius en aquest sentit, no se m’acut cap altra manera d’aconseguir-ho que contractar els serveis d’una persona que domini alhora la llengua original i la llengua de la traducció, i que al mateix temps estigui familiaritzada amb els requeriments del llenguatge teatral. Només si aquesta persona fa una lectura minuciosa de tot el text i el confronta amb l’original vostè podrà tenir una base sòlida per aprovar o rebutjar una traducció, a part d’estalviar als seus futurs traductors una pèrdua de temps i una humiliació innecessària.

A l’inici d’aquesta carta he esmentat el respecte com una de les prioritats que regeixen la meva feina com a traductor; hauria estat tot un detall per part seva si aquest respecte hagués estat recíproc.

Atentament,

Joan Sellent

Sabadell, June 12th 2012

Dear Mr. Albee,

About a year ago I was commissioned to translate your play A Delicate Balance for a specific production which premiered in Barcelona last autumn.

As has always been the case with all the plays I have translated for the stage, I undertook this task with the intention of being as respectful as possible. I believe respect is one of the priorities a translator should always have in mind, and that such respect has two main addressees: the original text (and by extension its author) on the one hand, and the potential audience on the other.

After I had finished my translation of A Delicate Balance I was informed about the obligation to submit to you, as the author of the original text, an exhaustive five-column grid with the detailed specification of —I quote literally from the e-mail sent by your agent— “any deviation from the exact English words and the explanation why this couldn’t be directly translated into Spanish, and why the words that were chosen were used.”

Allow me to expose the main reason why those requirements triggered in me the immediate impulse of not wasting a single minute in complying with them: I basically felt insulted as a professional at realizing that, after having worked as a translator for over thirty years, someone expected me to devote a hardly negligible part of my own time to a task that was as preposterous as it was useless.

As for the first part of the above statement —“any deviation from the exact English words”— I can assure you that, with the exception of the characters’ names and the odd place name or cultural reference, the rest of my translation is an absolute deviation from the exact English words, simply because it is written in another language. A language, by the way, which is not Spanish —as is erroneously specified in the quoted e-mail— but Catalan, which belongs to the family of romance languages and has enough differential features as to enjoy the status of an autonomous language with regard to Spanish or to any other in that family. Fancy the kilometrical length the grid would have attained if I had decided to meet such requirement literally.

As for the final part of your demands —“… why the words that were chosen were used”—, I could simply argue that the doubtful relevance of such a question (just imagine someone who doesn’t know your language asking you such question regarding an original work of yours) makes me rather reluctant to answer it, but nevertheless I shall leave my self-esteem aside and will make the effort: Mister Albee, the words that were chosen were used simply because the translator thought them appropriate.

You were perfectly entitled to fear I might have chosen and used some words that betrayed or distorted the meaning, the intention, the tone and the register of the original; I am not saying such fear would be altogether groundless, since translators that ill-treat and distort any text they come across are not scarce —but do you really think it possible that, had I been one of those, I would have made my misdeeds explicit in the grid I was being compelled to fill in?

If I finally gave in to your demands it was merely out of friendship with the producers of the play, who had let me know that, if such demands were not fulfilled, the author would stop the rehearsals and would not allow the play to be staged (which would have inflicted a very serious financial blow to that production company). Therefore I wasted some ten or twelve hours of my life on making up a number of pompous pseudo-philological explanations in order to fill in your grid; in other words, I drew up a list of utterly sterile absurdities from beginning to end. What I can assure you is that, if I had been aware of your demands before translating the play, I would have declined the commission with hardly a second thought.

Perhaps what I have written so far will make you suspect that I question the moral, intellectual and legal right of a playwright to have the final say whenever one of his plays is in the process of being produced. If this is the case, let me hasten to say that nothing could be further from my intention. I firmly believe in the legitimacy and importance of a playwright enforcing his authority, especially in this day and age when stage directors proliferate who, instead of being at the service of the text, tend to take quite a few hardly justifiable liberties and bestow themselves with an authorship that does not belong to them. Those stage directors who give themselves such author’s airs are indeed one of the curses of the present-day theatrical world.

And needless to say, I also regard as something totally legitimate the playwright’s right to control the translations of his plays before they reach the press or the stage. Of course I do. There are a lot of bad translations that, with their semantic mistakes and stylistic imperfections, represent an annoying burden a specific theatrical production may have to drag up to the stage and which is often in a big problem for the production and its audience’s reception.

However, when someone decides to enforce his rights —and now I am referring to any field of human activity—I should think that practical logic, common sense and the most elementary ethics would incline him to do it in such a way that is both clever and useful to his own interests, rather than offensive to the party that might supposedly endanger those rights. My personal experience of having had to translate this play of yours has made me see how pathetic authority can be when it is exerted in such a way that it’s of absolutely no use other than to gratuitously humiliate a professional who has tried to do his job as well as he can.

And allow me to be a bit repetitive: your way of exerting your authority as a playwright —at least as far as translations are concerned— is, from a pragmatic point of view, absolutely useless. The grids you compel your translators to fill in do not guarantee in the least the quality of a translation. Do you honestly think it possible that anyone who has done a bad translation will be able to detect his own translation mistakes and be as reckless as to enumerate them explicitly?

In order to guarantee some positive results in this sense, I cannot think of any other way of achieving that than engaging the services of someone who is both proficient in the source language and the target language and is at the same time familiar enough with the requirements of theatrical language. Only if such person does a detailed reading of the translation of the full text and confronts it with the original will you be able to have a solid base for approving of or refusing a translation, apart from saving your future translators a waste of time and an unnecessary humiliation.

At the beginning of this letter I mentioned respect as one of the priorities that govern my work as a translator; it would have been really thoughtful of you if such attitude had been reciprocal.

Yours,

Joan Sellent